Weaving LDCs into the fabric of the global economy

Integrating least-developed countries (LDCs), most of them located in Africa, into the global economy is one of the central challenges to fostering stability and spreading prosperity more widely across the globe.

These 48 countries account for a shockingly low 1% of world trade. The challenge to integrating them is especially acute in building roads and ports and reducing poverty. It is also crucial to deliver a dent in high youth unemployment, especially given that half of Africa’s population is under the age of 20. The infrastructure gap in Africa alone is estimated at US$90 billion annually.

To boost growth and development in LDCs, a major injection of foreign investment and a giant leap forward in global trade are needed. This can only be made possible through a deeper engagement with the private sector. While an impressive list of frontier markets, including Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia, have attracted large infusions of foreign direct investment in recent years, a fixation on growth alone will likely lead to a dangerous widening of income equality and damage to the environment.

To lift business investment and cross-border trade, LDCs must reshape their relationships with the private sector. They need to concentrate their reforms in several areas.

Focusing on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) makes sense for LDCs, since SMEs make up 90% of developing-country work forces. With 80% of global trade taking place in global chains, almost half of the value added in those chainscomes from local SME suppliers.

Partnerships with business to build and finance ports, airports and renewable power generation would transform economies and people’s lives while delivering long-term economic growth. LDC governments do not have the means to go it alone. To make these partnerships work requires a clear division of labour between the public and private sectors and a clear agreement on industrialization. Putting policies in place that attract foreign investment and uphold key principles, such as most favoured nation and national treatment, means foreigners and locals are dealt with equally in rights, benefits and privileges for imported and locally produced goods, as well as in international agreements.

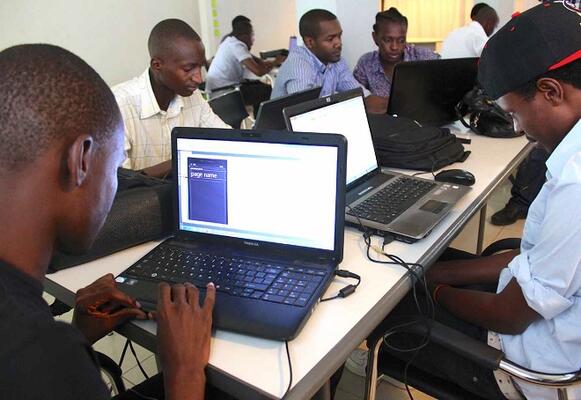

One of the greatest force multipliers for development comes from greater investment in information and communication technology (ICT), which can boost productivity by half and add substantially to gross domestic product (GDP). In fact, each 5% bump in GDP doubles the standard of living over a generation. As such, more widespread ICT access would create 150 million jobs for young Africans by 2020.

Another important step to bring LDCs into the global economy is to ratify and implement the World Trade Organization’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA). Improving border and customs procedures would – along with other elements of the Bali trade agreement to reduce global barriers to trade – can help create 18 million jobs in developing economies and assure consumers that perishable foods will not spoil, which is vital for the world’s poorest people.

Above all, though, business needs a stable, predictable investment and political environment, provided by robust, incorruptible institutions that endure. A public-private cooperation can help to create such an atmosphere by ensuring that each party benefits while not penalizing the other. Creating and maintaining predictable, transparent agreements and procedures such as those outlined in the TFA can provide an achievable means to that end.