Regional aid for trade

Aid-for-Trade flows have been affected by the recent crisis. But these flows are still significantly higher than they were relative to the 2002-2005 baseline period, and, despite the economic crisis, flows for the most part have been maintained. Resources devoted to building productive capacities have increased, a reflection of greater attention being devoted to private-sector involvement. In addition, Aid-for-Trade flows are increasingly directed toward low-income countries (LICs), rather than to middle-income countries.

Myriad studies show that international trade is essential to sustaining long-term growth and development, and to reducing poverty. Yet developing economies face market failures and binding constraints – from infrastructural shortcomings to bureaucratic impediments – that inhibit their ability to exploit fully the benefits of closer integration with the international marketplace. Recognizing this, member states of the World Trade Organization (WTO) launched the Aid-for-Trade Initiative at the Hong Kong ministerial conference in December 2005. The initiative is a development-assistance programme explicitly designed to improve the trade capacity of developing economies with the goal of improving inclusive growth and development prospects.

As reviewed extensively in Aid for Trade at a Glance 2013: Connecting to Value Chains, a joint publication by WTO and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Aid for Trade has so far made great progress in helping developing countries overcome supply-side constraints and infrastructural bottlenecks and connect to value chains. This is a demand-driven process in which recipient countries increasingly mainstream trade in their development planning and clearly articulate priorities. Donors have responded, and Aid for Trade enjoys strong and enthusiastic support from them.

With regional cooperation and integration becoming a top commercial policy priority for developing economies over the past decade, the potential role for regional and multi-country Aid for Trade has become increasingly prominent as a means of reducing trading costs with partners, facilitating the creation of regional production networks and integration into value chains. While the multi-country nature of regional Aid for Trade complicates its implementation and mainstreaming in national development plans, several studies, including Aid for Trade at a Glance, underscore its promise.

Weak economic growth and fiscal challenges in many OECD economies are putting pressure on government spending, and this again affects development cooperation. Aid for Trade is no exception. While Aid for Trade is a priority for the governments of OECD Member States, the initiative faces the same pressures as do other aspects of development assistance, underscoring the importance of tangible results and improving the effectiveness of Aid for Trade. This has clearly been a priority of the Aid-for-Trade Initiative – but in the current fiscal environment, which is still affected by the global economic crisis, it takes on a new urgency.

In 2011, overall official development assistance (ODA), excluding debt relief, fell for the first time since 1997. Hence, after several years of increasing Aid-for-Trade flows – even in the wake of the outbreak of the global economic crisis in autumn 2008 – the budgetary pressures stemming from continued economic weakness and debt issues had begun to take their toll. Almost US$ 41 billion was provided in Aid for Trade in 2011, a significant improvement since the start of the initiative, but down by 14% since 2010 (figure 1). In fact, Aid for Trade has increased by 57% since the agreed baseline for assessing progress (i.e. an average of Aid for Trade provided between 2002 and 2005).

Even in the middle of declining aid budgets and reflecting the increasing priority that donors attach to private-sector development, aid for building productive capacities actually increased in 2011 to US$ 18 billion, up 58% from the 2002-2005 baseline (figure 2). Agriculture, fisheries and forestry receive almost 60% of aid for building productive capacity. Aid for industry grew more strongly in 2011 than for other productive sectors and now stands at US$ 2.2 billion, 11% higher than the baseline.

Still, it is clear that the decrease in 2011 is concentrated in aid that supports economic infrastructure, such as transport, energy and communications (figure 3). Although infrastructure continues to receive the largest amount of Aid for Trade (53%), it declined by US$ 6.6 billion: from US$ 28.6 billion in 2010 to US$ 22 billion in 2011. This represents a 23% drop from the 2010 level, but remains 55.5% above the baseline.

Aid-for-Trade commitments were made to 146 countries in 2011. In terms of its distribution across income groups, LICs are now the largest recipient of Aid for Trade. While LICs experienced a 7% decline in commitments from 2010 to 2011, they were least affected by the overall decline, and flows to middle-income groups fell more sharply. At about US$ 14 billion, Aid-for-Trade commitments to LICs are now approximately double what they were during the baseline period. Africa was the most affected region in 2011, with a decline of 29% compared to 2010. This somewhat offset the impressive growth of recent years, as flows to Africa remain 64% higher than the 2002-2005 baseline.

While the outlook points to either stagnation or a modest decline in aid flows in the short run, the G20 has pledged to maintain Aid-for-Trade resources beyond 2011. On the basis of bilateral Aid for Trade and multilateral contributions, the G20 countries are currently on track to meet this pledge. In fact, OECD/WTO questionnaires suggest that most providers of South-South trade-related cooperation plan to increase their resources in the coming years. Collaborative private-sector ventures and value-chain investments are growing in number and impact, and are paving an innovative way forward for business involvement in trade-related capacity building. Regional Aid for Trade

While the economic literature supports the view that developing countries can accrue huge benefits from regional cooperation, the ‘groundwork’ of economic integration needs to be in place. This includes transport networks and other infrastructure, human-resource capacity, trade facilitation, and a trade-enabling environment for regional integration. The degree to which countries can benefit from regional integration will be a function of whether they can effectively overcome these constraints. Certainly there is a strong case for regionally focused Aid for Trade.

For example, African countries have for many years embraced a plethora of bilateral and regional accords. Still, the results have been disappointing, with intra-African trade remaining well below its potential. Studies have underlined that African countries fail to achieve regional integration because they lack the essential and underlying facilitating tools for economic integration. These include measures related to hard and soft infrastructure, capacity, trade-related information and contacts, and trade facilitation related issues. Many of these areas fall within the usual targets of Aid for Trade, but the multi-country nature of these accords complicates their resolution. Governments, it seems, tend to be hesitant about devoting resources to projects and programmes characterized by benefits that they are unable to capture fully themselves. In addition, implementing regional strategies is complicated by, inter alia, membership of overlapping regional organizations; lack of implementation of regional agreements; poor articulation within national strategies; and national and regional capacity constraints.

This is where regional Aid for Trade can play an important role. As is evident in the regional Aid-for-Trade case stories accumulated as part of Third Global Review of Aid for Trade: Showing Results (OECD-WTO, 2011), there are many areas in which regional Aid for Trade can address bottlenecks that impede regional integration, be it in the context of a formal regional accord or otherwise. In fact, relative to national approaches, regional Aid for Trade is most cost-effective in identifying regional projects with higher impacts, helping with project design and contributing to their implementation, in partnership with participating governments and other potential stakeholders, including the private sector. It can reduce costs associated with cross-border trade by providing financial resources and expertise to improve transport and infrastructure, streamlining red tape, enhancing capacity, improving cooperation across government agencies involved in regional trade, and addressing other bottlenecks. Improvements in these areas are necessary in order to create the best environment for countries to benefit from value chains, a proven driver of regional integration.

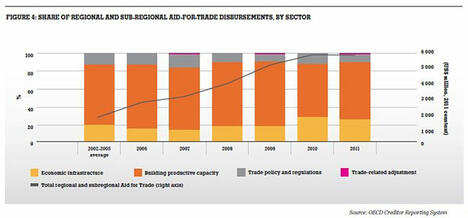

Regional Aid-for-Trade flows are small compared to overall flows but have been growing rapidly relative to the baseline (figure 4). In 2011 they came to roughly US$ 6 billion, and their share in total Aid for Trade has grown from about 9% in 2002-2005 to 12% in 2006 and 18% in 2011. While total Aid-for-Trade flows grew by about 50% in 2006-2011, regional and sub-regional Aid for Trade increased by 2.5 times as much. Thus, the importance of regional Aid for Trade is rising in line with the increase in developing-country regional cooperation initiatives. Regional Aid for Trade and value chains

The successful experiences of developing Asian economies underscore the critical importance of international trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) in development strategies. They show how production networks have been central in deepening the integration process and trade-FDI links. Regional production networks are being determined in large part by regional economic cooperation, and, in fact, they are driving the economic cooperation process. In turn, these production networks allow countries to participate in – and eventually move up – value chains, with pervasive salutary effects for socioeconomic development, ranging from reducing poverty to emerging from the ‘middle-income gap’. Hence, attracting and enhancing regional production networks have become explicit priorities of many developing-country regional organizations, from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations to the Caribbean Community.

There are already a number of case studies that show the effectiveness of regional Aid for Trade in supporting production networks (see, for example, the Third Global Review of Aid for Trade: Showing Results, OECD-WTO 2011). In addition, a 2013 survey of donors on how Aid for Trade is supporting intra-African trade carried out by WTO, the African Union, and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa concluded that regional Aid for Trade has focused successfully on removing the binding constraints to regional integration and on improving regional economic cooperation via improved hard and soft infrastructure. These same factors are essential to the creation of successful regional production networks.

Ensuring continued Aid-for-Trade flows in a fiscally challenging environment will require an ongoing focus on proper targeting and effectiveness. It is clear, though, that regional Aid for Trade constitutes a promising – albeit difficult – approach to boosting trade and inclusive growth in developing economies through support for regional production networks that have become a key catalyst of regional economic integration.

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not those of their respective organizations.